It was my birthday and I drank royal challenge whiskey and chatted with T at the Cosmo village. The music was loungy and she smelt nice, of soap and lavender. I leant forward about to say something witty when Aashi called and told me that Veerapan, the poacher bandit cop killing LTTE sympathizer who had eluded arrest for more than 20 years, who had killed over a hundred people and many more elephants, had been " shot dead " near Dharmapuri, a few hours away from Bangalore and close to the dense forests of the western ghats, the ether from where Veerapan he had handled his operations.

A few years previously I had been driving through Bandipur National Park and we had passed by another jeep driven by Krupakar and Senani, two wildlife photographers, who I was to meet in later years. The next morning, they were kidnapped by Veerapan and endured some weeks with him in the forest. Later another photographer friend told me about Veerapan and how he met him by accident, how he had taken his picture in the forest and I found myself wanting to meet him. I imagined him a romantic figure in wild settings, the smells of the forest in his nostrils, crouched in the bushes animal like, towering trees dripping foliage, dew everywhere, mist, elephants, just their wet black backs and heads visible through the leaves.

I decided that I would shoot the aftermath of his death. I asked T if she would like to come. It was 1 in the morning so she conferred with her parents on the phone. I took her home, she dressed suitably conservative and we headed out with some reporter acquaintances down deserted highways lined by dried up trees, towards the town. She was young, upper middle class and was leaving to New York to do a course in filmmaking, an unusual girl, who said wise things sometimes, I felt.

What memories, what quiet moments, what experiences with elephants and early misty mornings and immense beauties would have been with Koose Muniswamy Veerapan, forever lost with his death. Would he have taken them for granted? What horrors, rages and cold-blooded murders. A criminal, rebel, ruthless murderer, thief, loving husband, all of the above.

We reached Dharmapuri in the early morning. Swarms of mosquitoes gave the air texture when I ran my hand through it. I had a press ID with me and we walked past police barricades toward the morgue. Reporters were everywhere. The doors of the morgue were closed. The autopsy was being carried out.

Kannada daily photographers milled about, another day at the office and had gotten there early enough to shoot close ups of Veerapan’s head, bullet hole included. The constabulary read through the local papers, which included large pictures of his head. I went to the morgue. It was locked.

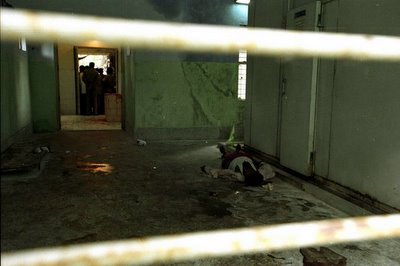

I went around the back to a window and opened it. A blood stained mortuary block. Men standing in corners with AK47 rifles. A man videotaping the autopsy. A policeman rushed forward and slammed the window shut.

We decided to go and look at the vehicle in which Veerapan had been shot. We drove to the site. The bullet-riddled van was covered with a large tarpaulin. Villagers walked by and a short distance away was parked the lorry in which the STF men had lain in wait. Bullets seemed to have riddled Veerapan’s vehicle from the quantity of glass lying about. A few bullets had hit the police lorry, from what seemed to be the wrong direction.

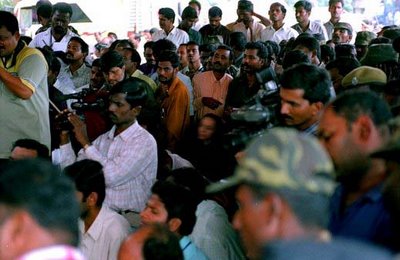

We returned to the mortuary. The cops had a tough time keeping cameramen at bay. Everyone wanted close up pictures of the bodies. I felt myself gagging at the odor that came from the morgue. Putrefaction, meat, blood and dettol. No one seemed to notice and jostled each other, fighting for a vantage point to take photos. The mortuary workers were excited. They posed, looking serious, clean and combed, by the bodies. Tomorrow they would be forgotten and would lapse back into the anonymity of small town India. Today they stood next to Veerapan, Bandit king, elephant killer.

I stood next to Veerapan. In a few days he would disappear from the news. In a few years his story would be lost, embellished and exaggerated about. His death would sink into local legend and eventually his bullet-riddled body would be worth just as much.The thief, murderer, poacher and brigand was being haggled over.

Veerapan didn’t look like himself. The photographs I had seen earlier showed a man, with piercing eyes and wild hair. Veerapan had been shot at close range in the head. I found myself not wanting to shoot his face stitched up, eyeball missing, hair carefully combed by the spruced up mortuary workers.

He police brass arrived in force, smiling, shaking hands and doing their hair with small pink and yellow plastic combs. They spoke to cameramen and many officers leaned in closer towards other officers so that they could be included in photographs. Constables pushed, shoved and strutted and commented on photographers “Look at that fellow, what stupid photos is he taking?” and shouted instructions. “You next, no.… YOU!”. A Karnataka STF member discussed with his friend whether, given their efforts they would also get plots of land as had been promised by the government of Tamil Nadu to the Tamil Nadu STF members who had killed Veerapan. The odour of putrefaction and dettol filled the air and I wondered if what was happening said more about our systems and our souls than just about Veerapan the dead dacoit.

I took some pictures of photographers taking pictures. I felt claustrophobic. I went to the rear or the morgue and forced opened a window. Through a doorway I could see the photographers shoot the neatly lined up corpses of Veerapan and his men. I was away, 20 feet apart from the chaos. A corpse lay on the floor, in the mortuary behind where the bodies had been lined up.

The corpse looked asleep. Who was he? He seemed to have bullet injuries from where I stood. An informer, an accident victim? A woman brought her dead baby in from the hospital. Reporters thinking she was related to Veerapan rushed at her cameras clicking and then rushed away. Another anonymous little corpse in an anonymous government morgue. The mother looked forlorn and resigned.

We left the morgue. Outside the gates hundreds of people stood on balconies and milled about waiting for a glimpse of the body. Veerapan wife was to come there soon. She had alleged that she had been tortured by the STF during their hunt for Veerapan. No one disbelieved her. It must have been hard for her to be married to Veerapan, I thought. She had joined him in the forest but for the most part they had remained separate. He had allegedly killed his own daughter, an infant, to prevent her crying and warning the STF of his presence. She spoke of her time in the forest fondly though, as I recall in a documentary, and she spoke of elephants and how she would watch them, with Koose Muniswamy Veerapan by her side.

I went to the nearby press conference under a tent. Outside the Tamil Nadu STF celebrated. They hoisted their leader on their shoulders and cheered. He fell off. I missed the photo as I was changing film. Men bonded and shouted and laughed on the TN side.The Karnataka STF made an entrance. They had been fierce competition and fights between the two state task forces when it came to apprehending Veerapan. The Karnataka STF looked forlorn and resigned. They had lost their baby too.

The press conference began. There was no room. T disappeared into the crowd. There was a lot of praise for the Tamil Nadu STF from the Tamil Nadu STF. The press guffawed a lot. No one seemed to believe that it was a genuine "encounter".

We got into the car, and slowly negotiated the packed roads. T lit up a cigarette. The crowds pressed up against the car, saw this and went crazy. They banged on the car and pressed their faces against the windows for a closer look. A woman smoking. I ran over a foot or two and drove home, back to Bangalore, past the same dried up trees, desolate fields and plastic packets blowing in the wind.

I felt removed from the masses of humanity who spoke different languages, stared at women smoking and crossed the road without looking in any direction. I was tired. I felt like I was watching myself drive from far away as we headed towards the city and its traffic jams. As with experiences that involve death and violence I wondered if one day I would be exaggerated, lied and embellished about. Or maybe like the baby in the government hospital forgotten. Would my mother be forlorn and resigned? Would morticians comb by hair with the same care? Why would they? Thus lost in thought, I nearly ran into a road divider.

We stopped at a roadside restaurant, I drank tea, lots of it and was awake again. T looked out of the window a lot and I sang songs in terrible Kannada to Bocelli playing on the car stereo and we drove past forgettable fields and similar towns under an overcast sky. She laughed and clapped her hands when I sang. I reached Bangalore and its traffic. I understood her need to leave India. She would not return I felt. Europe though, not America, I imagined. I stopped the car near her house, and wished her off. She smelt of cigarette smoke, lavender and sweat. She exited the car, walked down a lane and disappeared into the ether.

13 COMMENTS: